I’ve been disassembling Chawton House Library’s guidebook and handout down into Natoms, as the very first stage of my project there. Natoms are not my idea, but a concept from Southampton colleague Charlie Hargood. However, for my purposes I’ve distinguished between Persistent natoms (or P-natoms) which are physical and thus, for the a heritage visitor, stay in one place and do not change, and Ephemeral natoms (or E-natoms) which are not tied to a particular place or even form, they are any media which can be digitally transmitted and shared, such as text, video or music.

To break the guidebook that Chawton supplied down, I’m currently using Scalar, for reasons I explained in an earlier post. It took a little time for me to work out how I should best use it, and to be honest I think I might come unstuck when I start distinguishing between kernels and satellites, but right now I’m getting into the flow of it, so before I went too far, I thought it would be good to share.

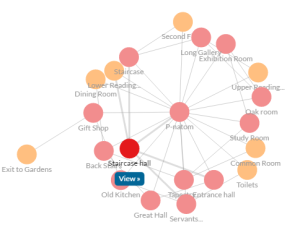

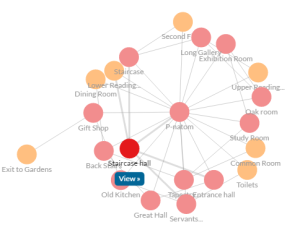

First of all I wanted to to some of the P-natoms in place. These are the rooms that our visitors will be exploring. It was very easy to list the rooms, and soon I had that list of rooms, each tagged as a P-natom, looking like this in Scalar’s useful “connections” visulisation:

But I had a slight crisis of confidence about how best to illustrate the links between spaces, or as Bill Hillier puts it, the permeability. Scalar allows simple hyperlinks, but doesn’t visualize them, or make them reciprocal. It also has a Path function, but that is only one way, really for stringing natoms together into a long-form text. So in the end I went for the program’s tagging function, which is quite sophisticated in distinguishing between items “being tagged” and “tagging”. Once I’d tagged the transitions betwene the listed spaces, my visualization looked like this:

I added the gardens at this point. I plan to keep my experiment within the walls of the manor house itself, but some doubt, or fear that I wasn’t future-proofing the model, made me put them in, as the exit form the gift shop.

These spaces are by no means all the P-natoms. More of the the collection will go in later. Next however I wanted to try adding some E-natoms. And that meant starting by breaking down the guidebook text. The first part of the guidebook was an essay, a brief chronological history of the place. Broken down into its constituent parts, and tagged as E-natoms, this is what that essay looked like:

As you can see, at this stage there is no connection between the the new E-natoms and the P-natoms, or between the story and the place. However, already some (but at this stage surprisingly few) of the e-natoms were suggesting engaging stories: which I’ve tagged “Literary Women” and “Jane Austen”. But look what happens when you start adding in parts of the collection, in the spaces in which they are displayed, and their associated stories. To two P and E-natom “solar systems” start to join together:

This is after the collection in just one space, the entrance hall, has been broken into the natoms. Its going to get a lot more complex as work progresses.