Following on from Thursday’s post on working with volunteers at Bishops House Sheffield, a second paper on the project has lots of very quotable stuff in its preamble. For those following along at home, this paper is: Claisse, Caroline, Petrelli, Daniela, Ciolfi, Luigina, Dulake, Nick, Marshall, Mark T. & Durrant, Abigail C.. 2020. Crafting Critical Heritage Discourses into Interactive Exhibition Design.

It starts off with a lovely quote about how the nature of museums changed as they became less about privately owned collections and more about public institutions: “Traditionally, museums are concerned with material cultures as their chief role is collecting and preserving artifacts for future generations, and to communicate what is known about those objects. The early museums were places where touching, holding and smelling were an integral part of the visit, a courtesy paid by the curator or the collection owner to their visitors or guests. By the mid 19th century, however, the personal, physical relation with the objects was gone, mostly because of the widening of the audience and therefore the changing mission of museums as public institutions”

But they go on to talk sing the praises of “house museums” which “offer interesting settings to explore the value of materiality in a context where a visually-driven ‘cabinets and labels’ approach exhibition design is not deemed appropriate.” They continue “Exhibition design in house museums goes beyond the curation and display of artifacts: the whole house is a historic object, meaning that content and container are one” which is a truism, but a very concise and apposite one. I do have to take issue with one thing they say however. They are wrong, or at least, conflating two things when they state “This type of house museums is described as ‘living history museums.'” The term “living history museums” often describes places that use costumed interpreters which, I would argue, the vast majority of house museums don’t – at least not on a day-to-day basis. The term is also used for the open air museums of buildings/folk/vernacular history such at The Zuiderzee Museum in Enkhuizen, and the Singleton Open Air Museum. Indeed it came be said that live costumed interpretation in museums started in places like those (though the Singleton museum resisted it for decades).

Another bit, with which I do agree, is their summary of Heritage as an aesthetic experience “Far from being perceived as boring and tiring, museums are, for many visitors, ‘restorative environments’ that, with their unique aesthetics, capture imagination and facilitate recovery from mental fatigue [26] [35]. Such aesthetic experiences are chiefly about being there. The aesthetic experience is not the experience of beauty – for it can be pleasant or unpleasant; it is characterised by intense attention, extended cognitive engagement, and affective responses.”

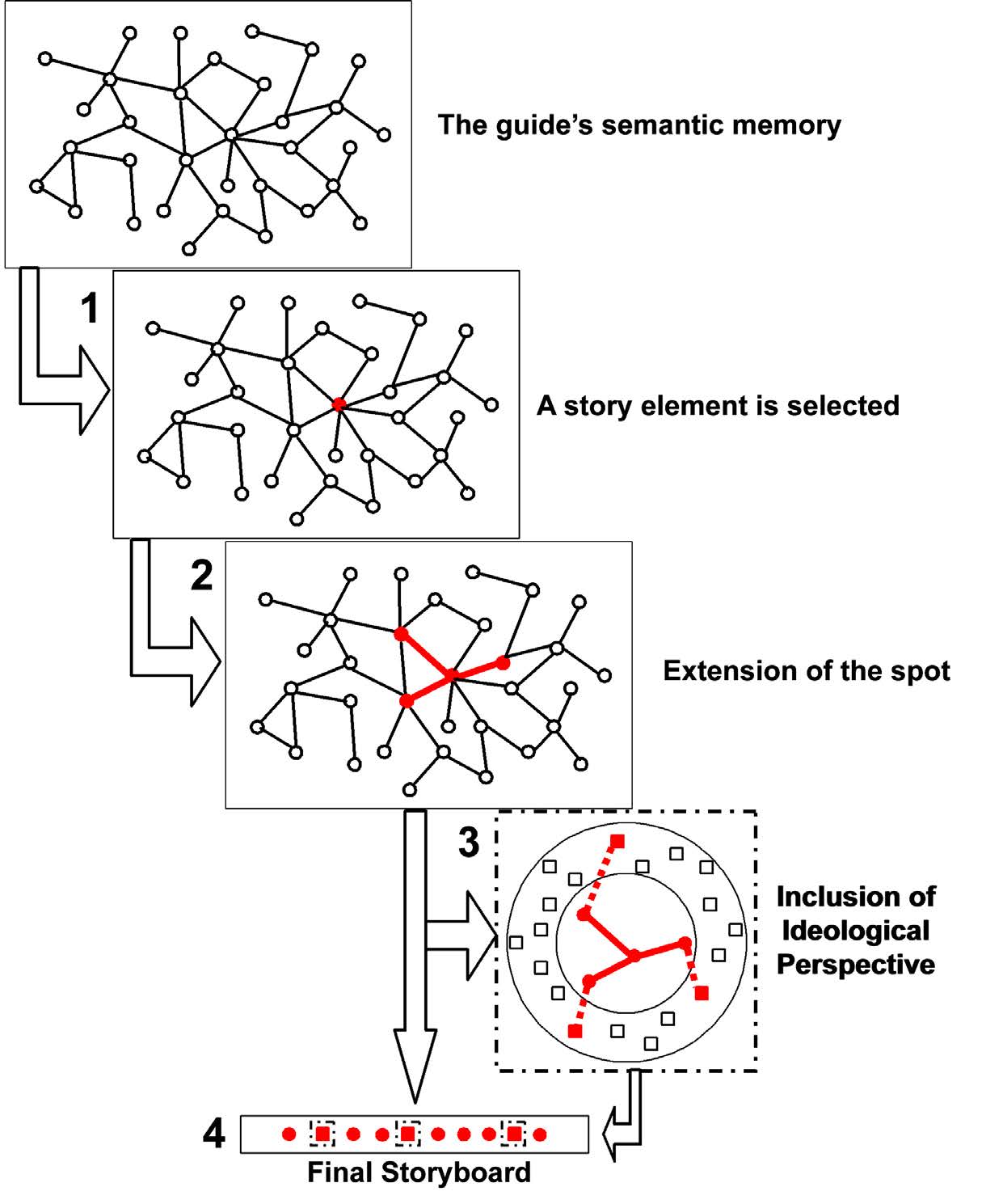

Of course one of the challenges to historic house storytelling is the existence of an implicit “‘authorized heritage discourse’ approach – a long-established orientation to heritage as understood and interpreted via the expert’s perspective, and tending to privilege the prestigious, universal and grand narratives” which is of course what I discovered which my Chawton experiment. What I noticed though, was not only that such a discourse is hard-wired into interpretive thinking, but that it might also be an outcome of visitor choices. It does not have to be so, but I would challenge their assertion that “The concept of heritage as a process that is actively constructed and recombined over time is particularly significant in the context of house museums where animators often dress up and enact characters to visitors: ‘It is this sensory experience of an embodied performance of a lifestyle that constitutes the process, through which heritage is both encountered and constructed.’” While excellent live interpreters can indeed challenge the “authorised heritage discourse approach” many more simply reinforce it, however in discussing that issue the authors a have a lovely turn of phrase which I am going to steal … I mean cite: “Exhibition design in a house museum can find inspiration from such an embodied storytelling that weaves the narratives with physical objects and social history, a game of performance and fiction within a specific physical space.” And again they elegantly put into words another truism that is not often expressed: “Staff and volunteers play an important role here, as they weave

stories and place by sharing with visitors a mixture of facts, speculation and anecdotes about the lives of previous residents. The meaning of the surrounding heritage emerges from the visitor-docent interaction process: visitors are expected to take part in the dialogue, to question and deepen their interests. In comparison, digital technology is easily seen as dry, a distraction from the actual place and curators of house museums are reluctant to introduce it.”

The evaluation of the project expressed in the conclusion identified four arguments “from heritage discourses that we found relevant for designing and reflecting on digitally-augmented exhibitions. We discussed the value of materiality, visiting as an aesthetic experience, challenging the authorized voice and heritage as a process.” The first two I have no problem at all with – I like especially their use of triggered scents to enhance the multisensory nature of the interpretation. I do challenge whether they really challenged the authorized voice, as I think the power of the dominant ideology and the expectations of the visitor for authenticity will have combined to confound the challenge but in one point I will say they did well – they used the power of fiction to create the narrative, they were not bound by fact. I will also argue that the visitor perception of heritage as a process might not be as great as they suggest it is – but again I will concede on point, they got visitors visiting spaces more than once to uncover the story. which is an impressive feat.