Let’s define it straight away: “‘stochastic’ being a fancy way to say ‘random’ and ‘unpredictable.'” That definition comes from Falk, J.H.. 2016. Identity And The Museum Visitor Experince. Oxford: Routledge, which is the very last bit of reading recommended by my external assessor that that I am writing about in this series of blog posts. I note its often cited in her own articles so I think its a heritage experience ‘bible’ she keeps close at hand. And its a good work, published after my literature review (it did include other Falk works), but one that addresses many of the gaps that I felt the review was missing revelations about visit motives that we knew within the National Trust through market research, but which were not expressed so clearly in the literature.

What Falk tries to do with this book is create a model for looking at the museum experience, which her says “is not something tangible and immutable; it is an ephemeral and constructed relationship that uniquely occurs each time a visitor interacts with a museum.” He starts though, with the visitor at the moment, before ether set foot on site, that they decide to make a visit. Their motivation is says is related to their identity (and we can have a number of identities. I, for example am a Cultural Heritage professional and a father. My reasons for deciding to visit a place will be different depending on which ‘me’ is making the decision. Falk says that identity related motives generally fall into one of five categories:

- Explorer – “The typical Explorer visitor perceives that learning is fun!”

- Facilitator – Facilitating parents and facilitating socialisers, both meeting the needs of others in their group

- Experience seeker – motivated to visit primarily in order to “collect” an experience, “been there, done that”

- Professional/Hobbyist – a tiny proportion of visitors but often much more influential

- Recharger – not a large proportion of visitors, but may be more regular visitors, as we discussed before

So where does ‘stochastic’ fit in? Well, Falk describes how each identity motivation has a trajectory to their visit.”Rechargers and Professional/Hobbyists probably have the “straightest” trajectories. These visitors typically enter with a fairly specific goal in mind, a relatively sophisticated understanding of the physical layout and design of the museum, and a fairly clear sense of how to accomplish their goals […] the trajectories of Explorers and Facilitators are much more generalized and less laser-like. The Explorer is seeking ‘interesting things’ while the Facilitator is seeking ‘interesting things for others.'”

Rechargers and Professional/Hobbyists “can and occasionally do get side-tracked by experiences outside of their initial intentions, but for these two groups, this is the exception rather than the rule. More often than not these visitors make a beeline to the exhibits or spaces they are interested in, spend whatever time it takes to accomplish their goal(s), and then depart. Although they may “graze” upon exiting, this is primarily to take

stock of things for their next visit.” But the Explorer is guided by “their own inner compass which is ‘magnetized’ by the visitor’s unique prior knowledge, experience, and interests. They can’t tell you what will pique their curiosity before they get there, but once inside the museum, they will know immediately what interests them!”

Facilitators “are primarily attuned to the social aspects of the visit; they are focused on what their significant other finds interesting and enjoyable. Facilitators […] tend to sublimate their own interests and curiosities unless they feel that by sharing these, they might be helpful in satisfying the needs and interests of others”

Experience Seekers come somewhere between the Explorer and Facilitator “but rather than satisfying their personal curiosity or the specific intellectual needs of their companions (though both of these are very likely to be strong secondary motivations), the Experience seeking visitor is in search of what is most famous and important in the museum. They have come to see the Hope Diamond or the Mona Lisa, or whatever the museum is most famous for.”

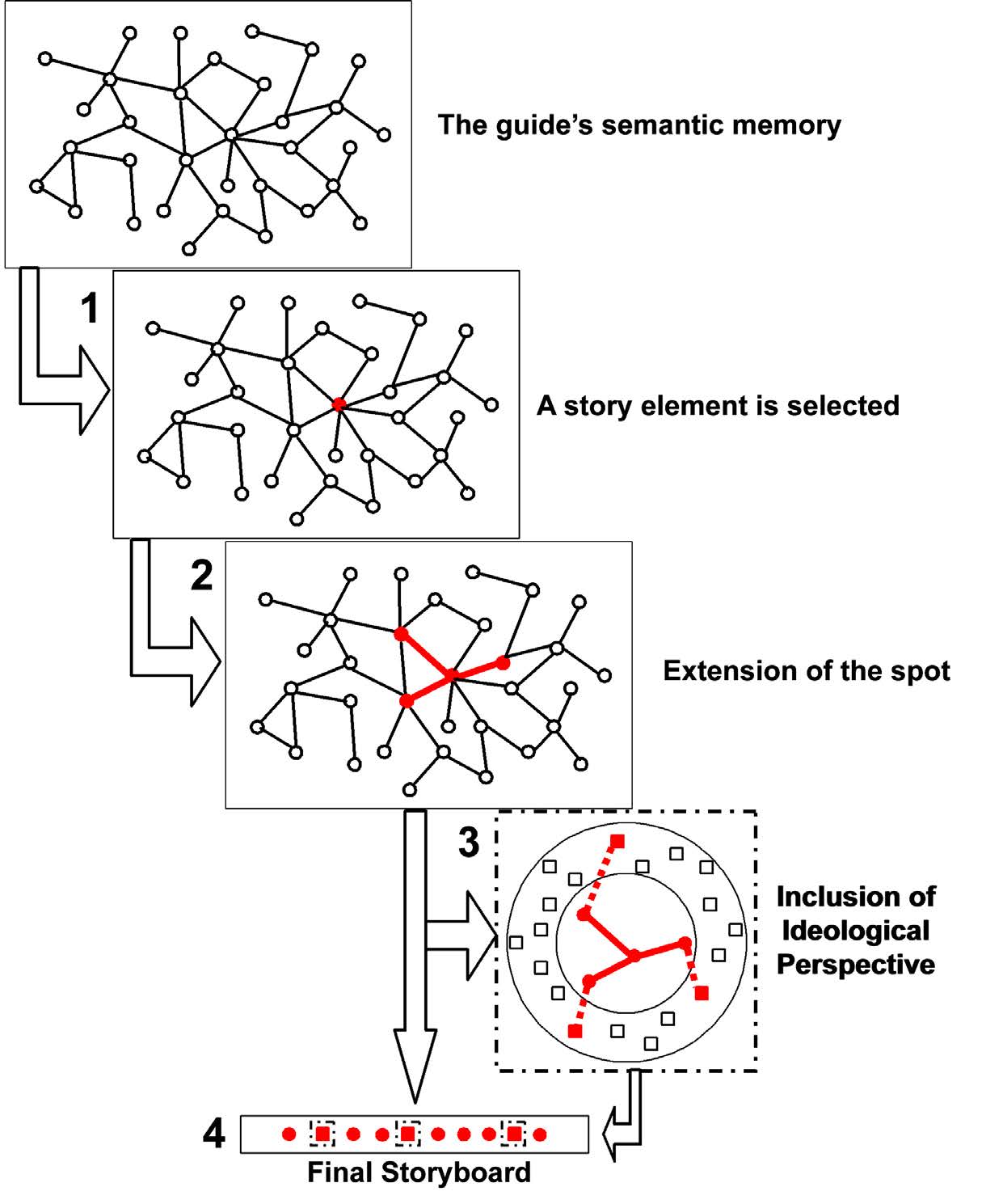

It’s important to note that whatever initial motivation a visitor has for going to a museum, they may well change to another one while they are there, depending on all sorts of factors – who they are with, something there see, all sorts of things. But Falk’s point I think is that Rechargers and Professional/Hobbyists are less likely to be distracted from their original motivation, and while experience seekers are somewhat more likely, they are on a tight timescale with other places to tick off their top ten list, so the groups most likely to make a stochastic visits are then Facilitators and Explorers. I think my Chawton experiment is deigned to respond to a guide stochastic visitors, so arguably more tied to these two visit motivations.

Finally, I love this quote about satisfaction surveys – its definitely something we noted at the National Trust:

Currently, the overwhelming majority of museum visitors find their museum visit experiences very satisfying. This is in part because the public has a fairly accurate “take” on museums and thus possesses relatively accurate expectations. It is also in part due to human nature; we have a propensity to want our expectations to be met and work hard, often unconsciously, to fulfill them, even if it means modifying our observations of reality to match our expectations.

page 159