Two papers today, because one of them doesn’t have much of interest, I think, to my corrections – it does have one great word however, which I will come to later. The first paper is another look at the project at the Bishops’s House in Sheffield that featured in previous papers and posts. This third paper, CLAISSE, C., PETRELLI, D., DULAKE, N., MARSHALL, M. & CIOLFI, L.. 2019. Multisensory interactive storytelling to augment the visit of a historical house museum. IEEE comes with lots of quotable quotes about the sort of environment I work in (until next month at least): “Unlike traditional museums, artefacts in house museums are displayed in domestic settings, out of their protective cases and with limited written interpretation. Due to this unique layout, they need to be understood from an experiential perspective: ‘stepping back in time’ or ‘standing in someone else’s shoes […] Digital technology is conspicuously absent, apart from occasional interventions relying on mobile phones. While using mobile phones does not affect the aesthetics of the historical heritage, any other digital technology intervention needs sensitive design, careful integration and planning.” which a pretty sweeping but generally true generalisation. One thing I am less certain of though is the authors’ assertion that historic houses “are looked after according to special practice identified as house museology.” For a start, museology is the study of museums, not a conservation (looking after) practice. I have worked in and around historic house museums since, well … since 1985* if you count my volunteering, and I have never heard the term “house museology’ with reference to looking after such place. Looking at the source for that assertion, I feel the authors are misreading what “museology” actually is.

However the next thing they say is abundantly true. “Spatial and aesthetic constraints mean curators have to choose which part of the story of the house is presented to the public. Thus house museums tend to concentrate on a single period in their history where both the building and its interiors are restored or reconstructed to match a particular era or episode in time. Such exhibition practice was recently criticized for limiting interpretation strategy to one linear narrative, often focused on a leading character.” And the finish off this introduction to the challenge of historic house interpretation with “Digital ntechnology offers new opportunities to bring these places to life. However, experiments have been limited to individual installations or temporary exhibitions”

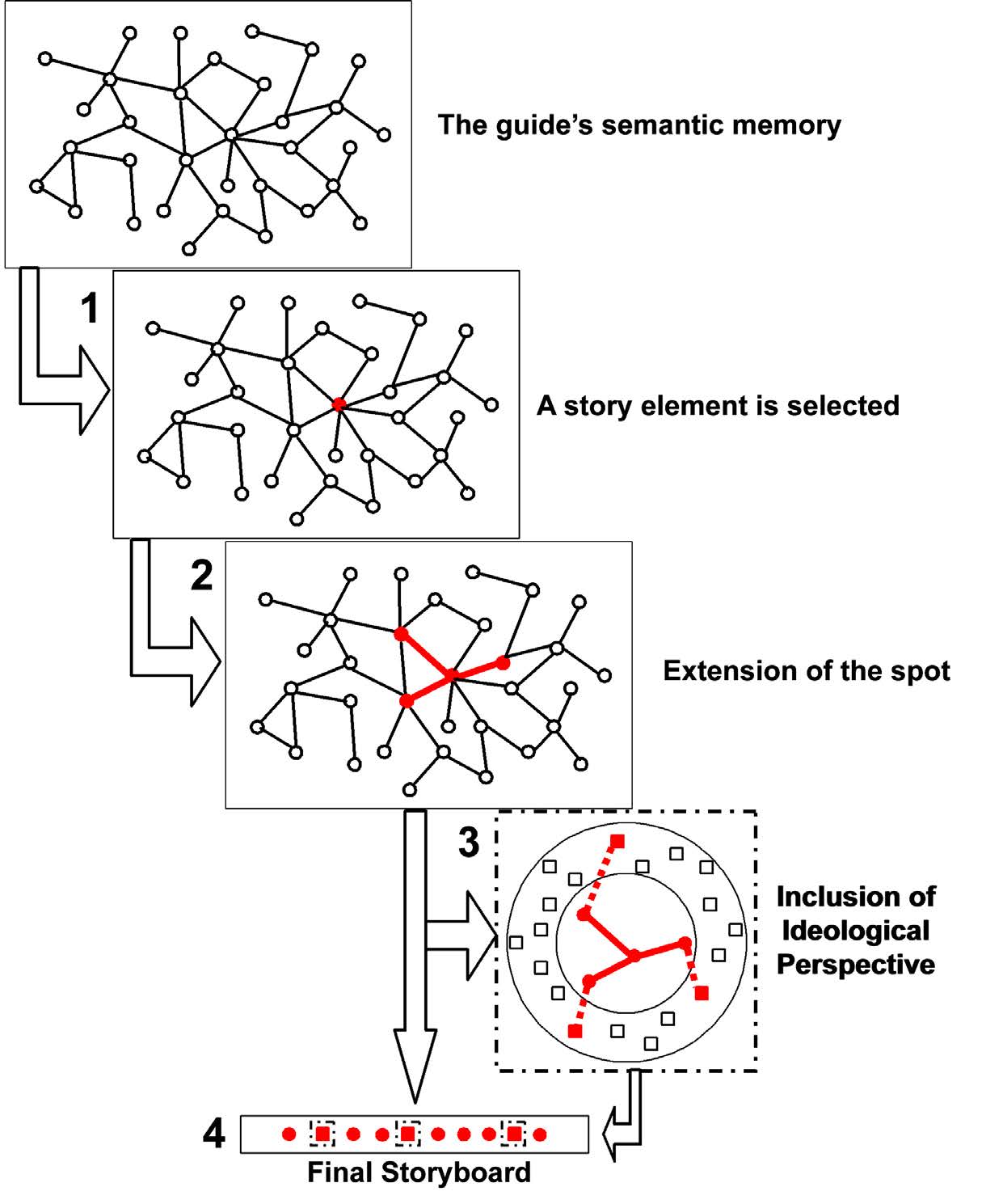

I won’t go into too much depth on what they did – my previous posts Gove more detail. But it is worth saying that actually what they did was create five “individual installations.” These were great, and I don’t want to dismiss them for their aesthetic qualities, or content, nor the process that went into creating them, but they are only a step on the way to a responsive environment. And of course they had to be activated by a tangible object with NFC tags, which I think adds an extra layer of complication to the interface which is not necessary. Having read about a number of these NFC-based tangible interactions now, and having been involved it one at Bodiam then only one where I think the object really added to the interpretation is the Votive Lantern offerings to the gods at Chesters. But these projects are indeed steps on the way to an ideal, and the ideal is described in the conclusion pot this paper: “the web of content is not embedded in a device, but distributed all around the house as objects and rooms, characters with their portraits, and the story they tell. It is the visitors moving around the House triggering content, observing and discussing that make this an interactive storytelling in place […] it gives opportunities for volunteers [people, would be a better word I think, including staff, visitors etc] to take ownership of the place and sustain participation over a longer period of time by generating new content and uploading new stories.”

There were fewer quotable quotes in the second paper: Ardito, Carmelo, Buono, Paolo, Desolda, Giuseppe & Matera, Maristella. 2018. From smart objects to smart experiences: An end-user development approach. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 114: 51-68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2017.12.002. Which talked about tools for non technical staff to create interactive narratives. Its useful stuff but in my corrections I think a reference to the paper will be enough. There is one useful phrase though which I feel I might need to insert – which I think is second nature to HCI people but not to Cultural Heritage staff, though I think its easily understood and that is “Event-Condition-Action (ECA) rules”

Oh and I also like to this quote introducing MeSch, which I have already written about in my thesis but light add in “Very few contributions in the literature address the possibility of enabling CH experts to shape up smart visit experiences. One prominent approach is the one proposed by the meSch project, which aims to enable CH professionals to create tangible smart exhibits enriched by digital content. The peculiarity of

the meSch approach is that it does not require IoT-related technical knowledge: the platform offers an authoring tool where physical/digital narratives can be easily created by composing digital content and physical artefact behaviors.”

*Ouch, that feels like a very long time.

In a pleasant surprise today, a new book dropped through my letterbox.

In a pleasant surprise today, a new book dropped through my letterbox.